Giant Water Bug is a fascinating species, but it is declining across the country, and we have fewer opportunities to see it up close. Let’s take a look at Giant Water Bug photos from different angles and enlarge them to see the details.

Giant Water Bug is found all over the world, but the one in this article is from Japan, scientifically named Kirkaldyia deyrolli. Kirkaldyia deyrolli is a largest aquatic insect in Japan, with a body length of nearly 7 cm.

Giant Water Bug has been a protected species in Japan since 2020, but hobby keeping is not regulated.

Photos in this article can be used in various media with credit to @gengo6com. If the article is to be published on the Internet, please link to https://gengo6.com/. For TV media, please let me know in advance which program will be aired and when.

Photos of adult Giant Water Bug

In the photo below, the Giant Water Bug has a white cottony water mold on its proboscis. This is common in captivity, but does not seem to affect them to the point of death.

Most of the world’s Giant Water Bugs belong to Lethocerus. Japanese Giant Water Bug used to be classified as Lethocerus, but due to its large forelegs and long claws, it became independent as Kirkaldyia deyrolli.

Photos of mating and egg laying of Giant Water Bug

The Giant Water Bug is an ambush species and usually does not move much, but during the breeding season, it actively moves to find a mate.

Males of the Giant Water Bug call for females by pumping the surface of the water, leading to mating.

Mating of Giant Water Bug is carried out intermittently during spawning. Males mate many times, getting off and Mating in the Giant Water Bug is intermittent during spawning. The male mates repeatedly while climbing down and up the pole.

Giant Water Bug’s genitalia.I don’t know what’s going on.

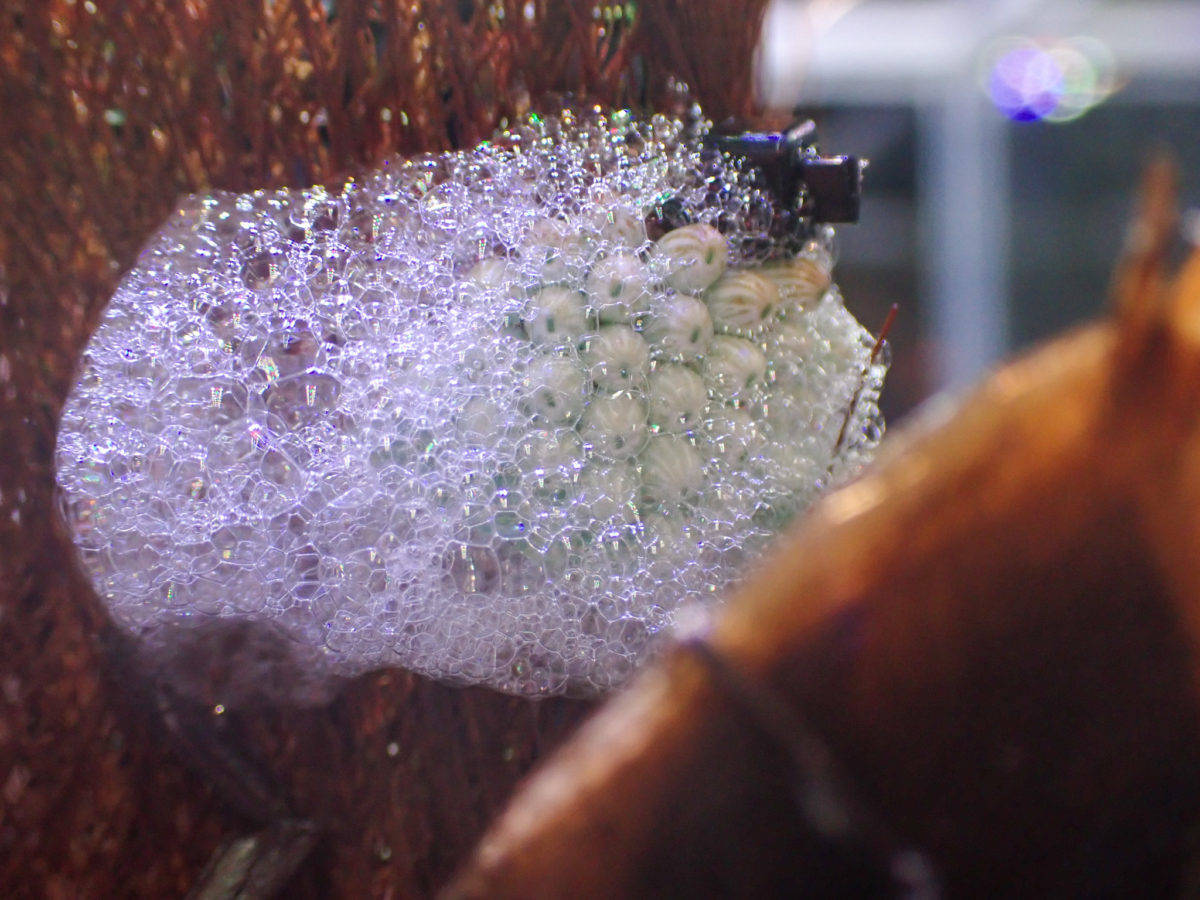

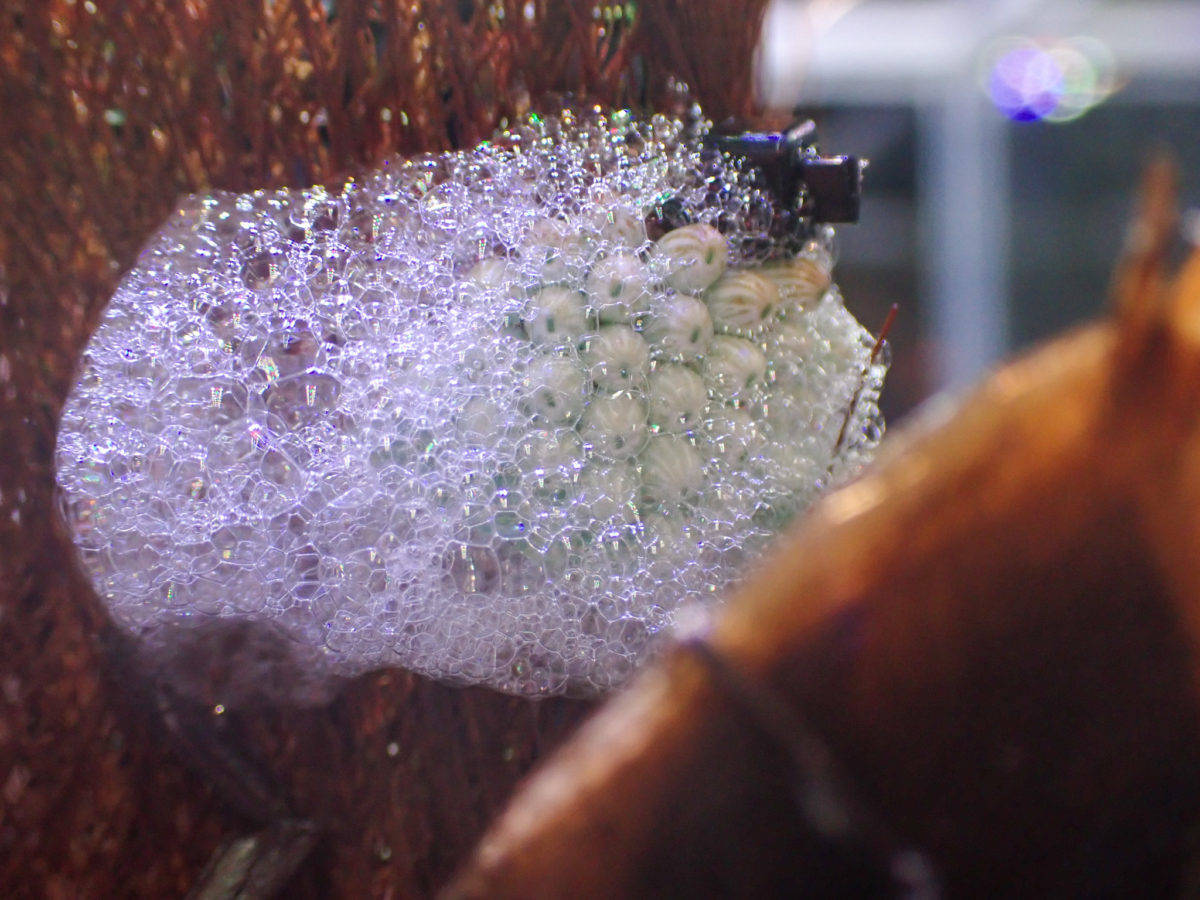

Giant Water Bug lays its eggs in bubbles, which disappear some time after spawning. There seems to be another object that attaches the egg mass to the pile.

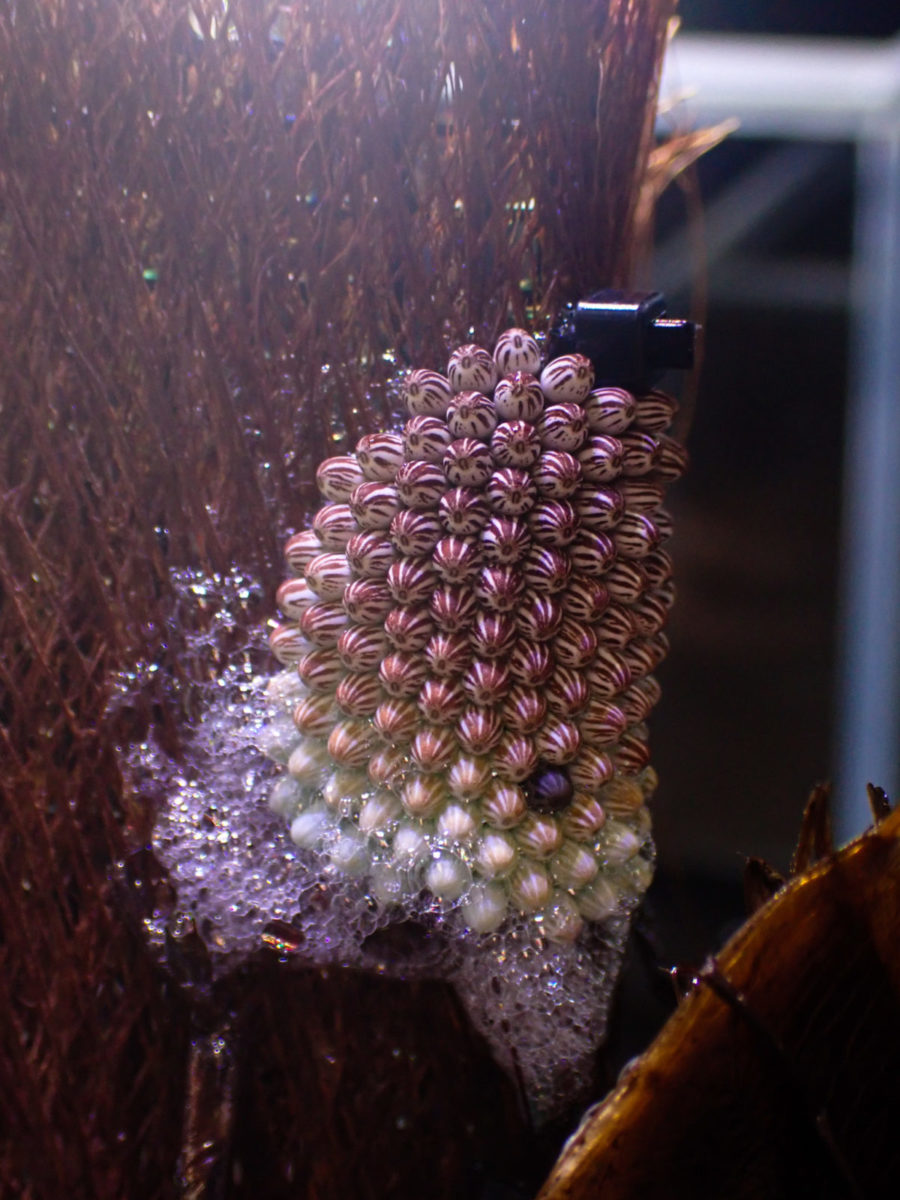

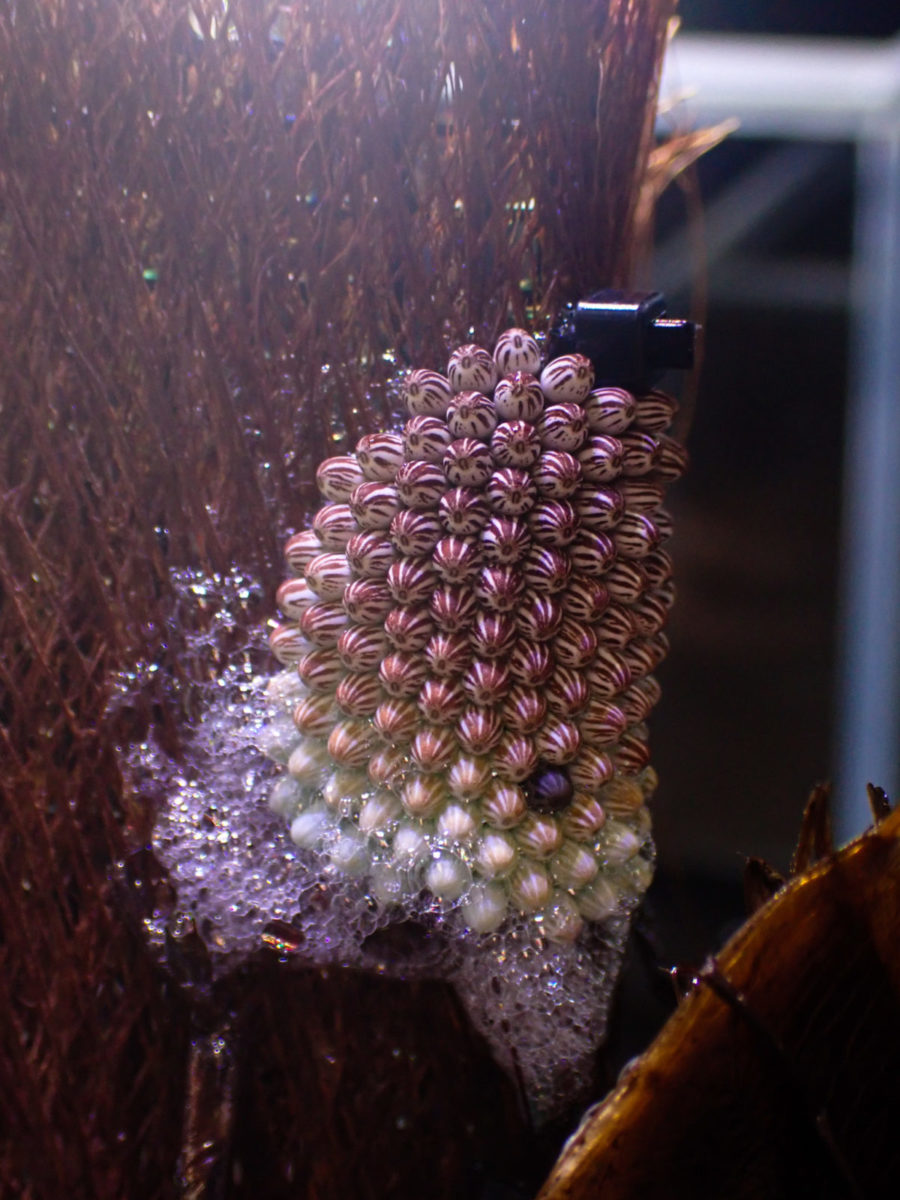

Giant Water Bug forms egg masses and lays its eggs from the top down.

In the photo below, one of the eggs is darker than the rest, and it looks like it’s sterile.Not all Giant Water Bug eggs hatch.Sometimes the hatch rate is as low as 50-70%.

Egg mass destruction by a female Giant Water Bug

The destruction of egg masses by female Giant Water Bugs is a frequent occurrence in captivity. Unless the egg masses (and the males protecting them) are isolated, it is safe to say that they will be destroyed first.

The female attacking the egg mass and the males to protect fought and knocked down the struts. After that, the female In the photo below, a female turtle attacking an egg mass and a male protecting it fought and knocked over a post.

The female then sucks the eggs for sustenance, and the male also resists at first, but is often driven away by the larger size of the female.

Extra. A chaotic photo of a pair of Giant Water Bug laying eggs and another individual eating a loach.

Giant Water Bug sometimes feed on the water to prevent others from taking their food if the surroundings are noisy.During spawning, the male climbs up and down and makes a lot of noise, so I think this is what happened.

Photos of Giant Water Bug egg masses and their hatching.

It is well known that male Giant Water Bugs are protective of their egg masses, but they don’t stick around all the time. They may be found at the base of a support pole, and climb up when stimulated.

Even though they are aquatic insects, Giant Water Bug are not completely adapted to living in water, and lay their eggs on the water. They lay their eggs on the water, and if the eggs are not watered, they will dry up and not hatch. Water supply by the male or a human is the key to development.

Eggs of Giant Water Bug basically expand every day. A deflated egg is a damaged one.

Eggs of Giant Water Bug are green immediately after spawning, and then brownish streaks appear. These gradations appear because the eggs are laid in order from the top.

Giant Water Bug larvae do not always hatch in unison, although they are famous for their simultaneous hatching photos.

However, Giant Water Bug larvae do not always hatch at the same time. In captivity, they may hatch in different stages, depending on the lighting conditions. In this case, the hatching rate is often extremely low, such as less than half.

The hatched Giant Water Bug larvae fall into the water. Yellow one in the photo is just after birth. A few hours later, the striped pattern unique to the first instar larvae emerges.

Photos of Giant Water Bug larvae

The larvae of Giant Water Bug are characterized by a large variation in color and pattern from one stage to the next. In particular, the first instar larvae of Giant Water Bug are striped blackish-brown in color, which differs from the greenish body color of the second instar and later.

Giant Water Bug grows quickly and is capable of feeding on prey more than twice its length immediately after birth. It is also common to see multiple Giant Water Bug larvae attached to a rampaging prey.

The photo below shows the first instar larva of a turtle attacking a killifish. The belly is swollen.

One of the reasons why the first and second instar larvae are so prone to death is that some of them are born in groups of 50 or more, so they do not get enough food. Giant Water Bug larvae with floppy and thin abdomen are not getting enough food.

Immediately after molting, Giant Water Bug larvae glow emerald green, but after a while they return to a more subdued color.

Some books say that Giant Water Bug larvae are cannibalistic and should be kept individually, but young larvae can be kept in groups. They frequently overlap each other, and I have the impression that they do not actively cannibalize each other.

In the case of insufficient food, the young larvae simply die, and cannibalism tends to occur when they become about four or five years old.

The second instar larvae of the Giant Water Bug are gourd-shaped, but when they reach the third instar, their width increases.

Giant Water Bug larvae are larger and more numerous when they reach the third instar stage, so they fill up their rearing containers.

In the case of the Diving Beetle larva, the body segments grow longer, but in the case of the Giant Water Bug, as it grows, the upper and lower parts of the body become thicker and swell up like a water bottle before finally molting.

In the photo below, the pronotum is already cracked and the Giant Water Bug larva has begun to molt.

Key to success in the Giant Water Bug larval molt is the clean exit of the legs. The larvae that become defective due to the leg tips getting caught, for example, almost never survive.

Giant Water Bug has sharp claws on its front legs, but as a larva, it has two claws.

GGiant Water Bug larvae breathe by storing air in their abdominal cilia. In captivity, there are quite a few individuals that die from respiratory failure. It is also effective to use a filter to reduce the frequency of water changes.

Spiracles of the Giant Water Bug moves to the abdomen as a larva and to the back as an adult. Each black dot near the edge of the abdomen is a pneumatome.

Wings of Giant Water Bug do not increase in size with each larval stage, but suddenly and prominently protrude at the fifth stage.

Giant Water Bug’s diet consists of extracorporeal digestion, in which digestive juices are injected into the food to dissolve it. The mouth moves freely.

The 5-larva of Giant Water Bug changes reddish-brown with the approach of emergence.

The photo below is a female because it is large and wide.

Giant Water Bug larvae have a different body size when they reach the 5th instar stage, and it is possible to determine male and female.

Giant Water Bug hatching photo

It takes about 40 days after hatching for a Giant Water Bug to become an adult.I observed the Giant Water Bug 5th instar larvae hatching! It takes about 20 minutes for neoteny to be born.

The photo below shows a Giant Water Bug 5th instar larva with its back cracked and molting started.

The larva shakes its body and pulls out its upper body.

Wings grow in parallel with the molt.

Adult Giant Water Bug breathes by storing air between its back and wings. For this purpose, its back is densely covered with fine hairs.

Neoteny is pale in color for a while, but gradually becomes darker. The body remains soft for a few days.